In the late 19th century, the bicycle wasn’t just a mode of transport, it became a powerful symbol of women’s liberation. While male inventors and industrialists were shaping the mechanics of the bicycle, it was feminist inventor and suffragist Henrietta Müller who helped shape how women experienced it.

Henrietta Müller (1845/6–1906) was more than a suffragist and social reformer, she was a pioneering inventor who understood the power of design in challenging societal norms. Born in Chile to a German father and English mother, Müller pursued higher education at Girton College, Cambridge, studying Moral Sciences at a time when women's access to education was limited. She later founded and edited the Women’s Herald, a progressive newspaper aimed at the "thinking woman," fostering critical discussions on women’s rights and social justice.

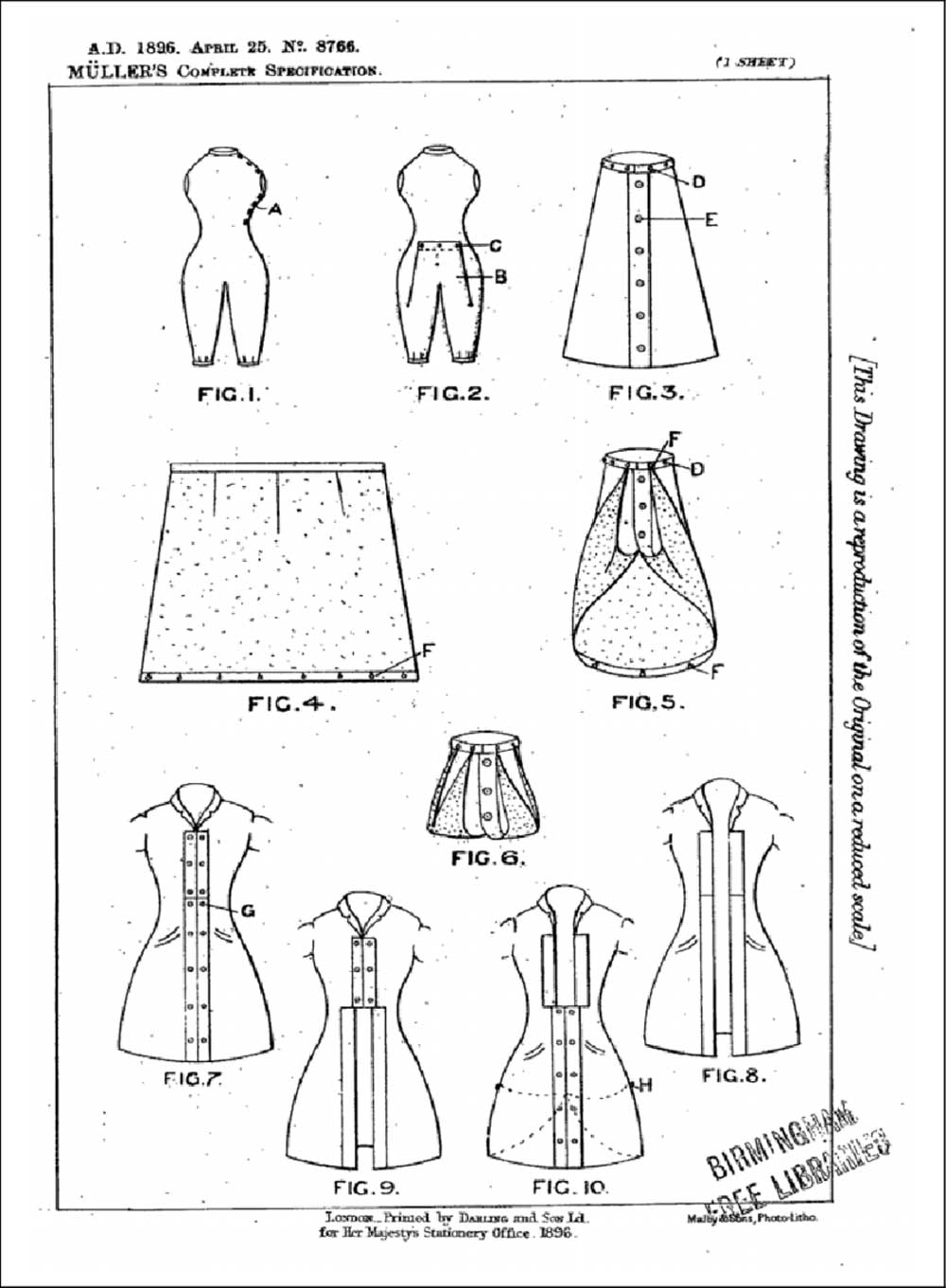

In 1896, Müller patented a revolutionary three-piece cycling suit designed specifically for women. This ensemble comprised a tailored jacket, an A-line skirt with adjustable loops to raise its hem, and an all-in-one undergarment combining a blouse and bloomers. The design allowed women to transition seamlessly between walking and cycling attire, offering both practicality and modesty, two essential factors for any woman in Victorian society daring enough to ride a bicycle.

Clothing as a Catalyst for Women's Liberation

Müller's invention was not merely about comfort; it was a bold statement against the restrictive clothing norms of the Victorian era. At the time, traditional women’s fashion involved heavy skirts, tightly-laced corsets, and multiple layers, all of which severely hindered mobility and posed significant safety risks when cycling. Müller's design offered an alternative that was not only functional but quietly revolutionary, promoting ease of movement and autonomy in public life.

One of the most radical aspects of her cycling suit was its inclusion of five pockets—a rarity in women’s clothing of the era. In a time when female garments were intentionally designed to limit functionality, Müller’s emphasis on utility signalled a broader feminist ideology: women deserved the same practicality and independence that men took for granted. She even encouraged wearers to add more pockets, emphasising that clothing could serve as a tool of empowerment. By patenting her design, Müller declared that women had the right to innovate, to own intellectual property, and to redefine how they moved through the world—literally and figuratively.

The Bicycle: A Symbol of Feminist Progress

By the late 19th century, the bicycle had become an unexpected yet powerful symbol of feminist progress. As more women began to cycle, it became clear that traditional attire was incompatible with the activity. Innovations like Müller’s cycling suit directly addressed these barriers, allowing women to embrace the freedom and independence that bicycles offered.

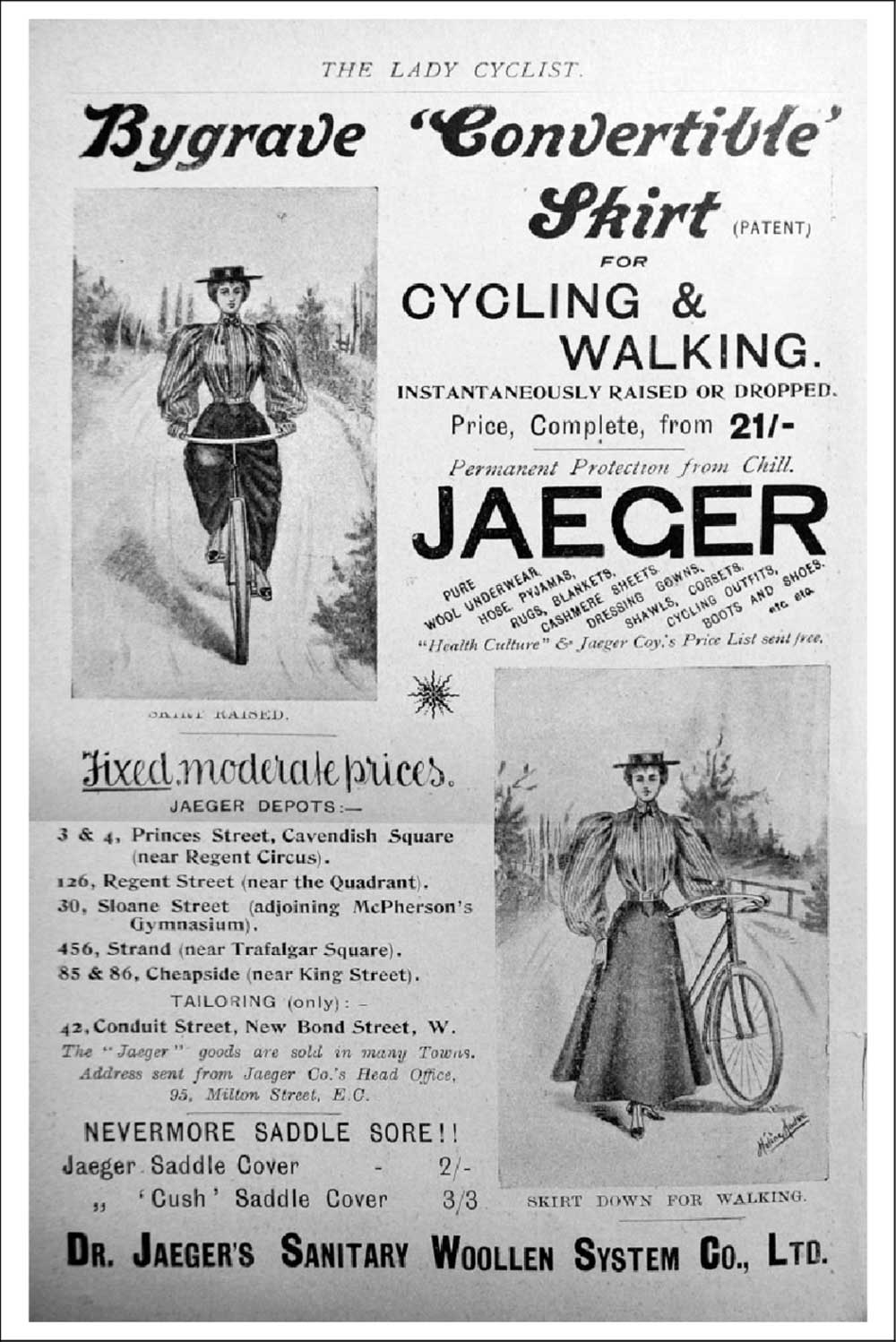

Müller was part of a larger wave of women inventors who transformed fashion into a form of protest. Alice Bygrave, for example, patented a convertible skirt in 1895 that used a pulley system to lift the hem for riding. Julia Gill and the Pease sisters followed with similarly innovative garments. These designs went beyond aesthetics—they provided women the physical freedom to engage in public and recreational life, all while challenging the restrictive ideals of femininity.

A Spiritual Journey: Müller’s Profound Connection to India

Henrietta Müller's vision extended beyond Western feminism, her life took a deeply spiritual and cross-cultural turn through her connection to India. In the 1890s, Müller became associated with the Theosophical Society, embracing a blend of Western mysticism and Eastern philosophy. She traveled extensively across India, engaging with spiritual and social reform movements. Most notably, she formed a close alliance with Swami Vivekananda, the Hindu monk who brought Vedanta and Yoga to the West.

Müller played a pivotal role in supporting Vivekananda’s Ramakrishna Mission, helping to purchase land for Belur Math, which remains the mission’s headquarters to this day. Her philanthropic spirit also extended to the personal, she adopted a young Bengali boy, Akshaya Kumar Ghosh, and supported his education at Cambridge University. This aspect of her life reveals Müller as a rare bridge between East and West, contributing to India’s intellectual and spiritual renaissance while reinforcing her lifelong commitment to justice, equality, and holistic reform.

Henrietta Müller's legacy is a compelling reminder that progress often begins with the seemingly mundane—like what we wear. Her cycling suit was not just a garment; it was a political tool, a declaration of independence, and a catalyst for societal change. By reclaiming comfort, functionality, and intellectual ownership, Müller and her contemporaries didn’t just make it easier for women to ride bicycles, they helped women ride into new roles in society. Her story illustrates that innovation, when guided by purpose, has the power to change not just fashion, but the future.