There are many things that hinder women from getting something as basic as an education. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) says that poverty, geographical isolation, minority status, early marriage and pregnancy, gender-based violence, and traditional attitudes about the status and role of women are among the many obstacles that prevent women from fully exercising their right to participate in, complete, and benefit from education. The result, the UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics reveals, is that there are 16 million girls in the world who will never set foot in a classroom.

Why men need to play a role in women’s education

Women also account for two-thirds of the 750 million adults without basic literacy, indicating that while boys in some regions of the world are equally disadvantaged, lack of access to education plagues girls more, clearly. What’s equally evident is that to bring about concrete global changes, and bridge this gender gap in education, engaging men and boys in gender transformative programs or initiatives is of vital importance. This is primarily because women’s empowerment is not a goal that can be achieved in a vacuum.

The everyday inequality and discrimination women face is directly associated with our relations with men, especially when it comes to accessing resources and decision-making. It’s therefore quite logical that eliminating these inequalities require equal, if not more, efforts by men and boys.

Now if you’re assuming this is a new-fangled idea, think again. History is testament to the fact that enlightened men—men who see women as equal partners with unlimited potential rather than subjects or objects to control—have played a huge role in helping women find their voice, make their stand and march towards liberation. Don’t believe us? Here’s a quick look at five famous men in history who helped Indian women actively, and throughout their lives, in getting an education. Do present-day men and boys need to look any further for inspiration? We think not!

The leaders who fought for women's education in India played a crucial role in advocating for gender equality, social progress, and educational reform. Their efforts and contributions are of immense importance for several reasons:

Gender Equality: Leaders who championed women's education recognized the fundamental principle of gender equality. They believed that women deserved the same educational opportunities as men and worked to break down barriers to achieve this equality.

Empowerment: Education is a powerful tool for personal empowerment. By advocating for women's education, these leaders enabled women to gain knowledge, skills, and self-confidence, which in turn led to greater independence and decision-making abilities.

Social Reform: Many leaders advocating for women's education were also involved in broader social reform movements. They saw education as a means to address and reform various social issues, including child marriage, dowry, and women's rights.

Economic Contribution: Educated women are more likely to participate in the workforce, contributing to the nation's economic growth. Leaders recognized that an educated female workforce could positively impact the country's economic development.

Enhanced Quality of Life: Education leads to better health awareness, improved living standards, and greater social well-being. Leaders who supported women's education aimed to enhance the overall quality of life for women and their families.

Progressive Ideals: Advocating for women's education was often part of a broader set of progressive ideals. These leaders pushed for social change, human rights, and a more inclusive and equitable society.

Cultural Preservation: Education empowers individuals to preserve and share their cultural heritage. Leaders recognized that educated women could contribute to the preservation of cultural traditions and the passing down of knowledge to future generations.

Leadership and Participation: An educated female population can lead to greater participation of women in politics, decision-making, and public life. Leaders recognized the importance of women's voices in shaping the nation's future.

Long-Term Impact: The impact of advocating for women's education extends beyond a single generation. Educated women are more likely to prioritize education for their children, creating a positive cycle of learning and development.

Global Competitiveness: In a globalized world, the education of women is essential for a country's competitiveness and growth. Leaders recognized that a well-educated female population can contribute to a nation's success on the international stage.

Legal Reforms: The efforts of these leaders led to legal reforms that supported women's rights, such as the right to education, property rights, and protection from discrimination.

Inspiration: The legacy of these leaders continues to inspire future generations to pursue education and gender equality, creating a lasting impact on society.

The leaders who fought for women's education in India were instrumental in challenging societal norms, advocating for policy changes, and ultimately paving the way for a more inclusive and equitable society. Their work remains an important part of India's history and an ongoing source of inspiration for the global fight for women's rights and education.

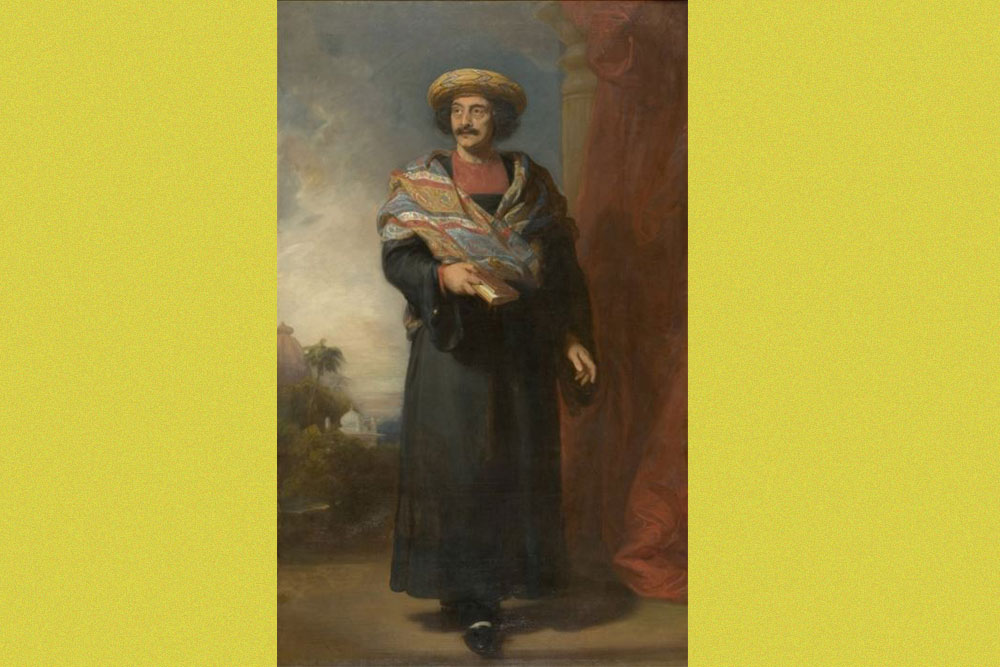

Raja Ram Mohun Roy

You may know this 19th century social reformer as the leader credited for the abolition of the Sati pratha—where a widow is burned alive on the funeral pyre of her dead husband—but there’s a lot more that Raja Ram Mohun Roy accomplished during his life. When it comes to education reform, Roy was one of the leading Bengali intelligentsia who believed in teaching Indians Western science, literature, philosophy and medicine. Not only was he one of the founders of major educational institutions like Hindu College (later known as Presidency College), the City College, and numerous English Schools across colonial Calcutta, but also advocated the need for educating women.

Education Indian women was already a target set by Christian missionaries, but it was Roy who helped popularize the concept among the elite Hindus. His argument against those naysayers who believed educating women was against Hindu culture was to delve into the shastras and prove that women’s education formed a core of ancient Hindu traditions, and had led to near-mythical women scholars like Gargi and Maitreyi. The Brahmo Samaj, which was founded by Roy, worked tirelessly to remove these stereotypical, popular prejudices against women’s education. In fact, most of the girls’ schools that later emerged in Bengal were deeply influenced by Roy’s decades worth of campaigns for women’s education and other rights.

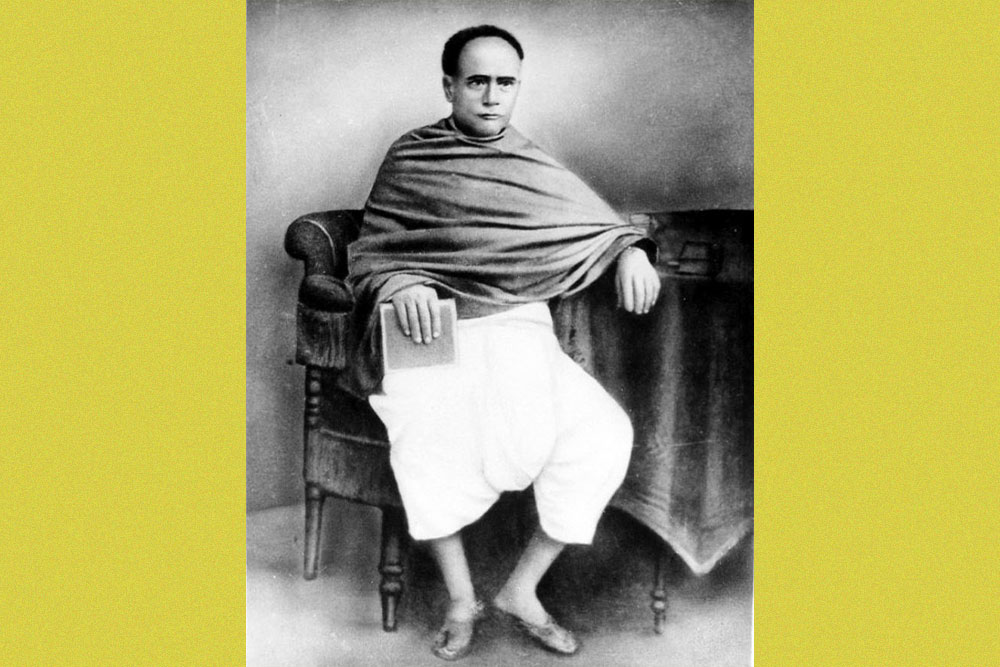

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar

Quite like Roy, school textbooks celebrate Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar as the Indian reformer behind the Widow Remarriage Act of 1856. What many don’t know is that Vidyasagar was a social reformer who understood that a mere act of legislation cannot change the fate of women in the country, nor would it help women fight centuries of social oppression. Educating women was, therefore, the larger, lifelong goal he tireless worked towards. As one of the leading educators of the time, Vidyasagar held power to lobby for schools for the Indian girl child, and the fact that he exercised this power to the hilt is a fact that cannot be denied.

Vidyasagar organized a fund called the Nari Shiksha Bhandar, and led door-to-door campaigns asking families to allow their daughters to be enrolled in schools. He frequently campaigned for women’s education through contemporary English and Bengali publications like the Hindu Patriot, Tattwabodhini Patrika and Somprakash. He not only opened 35 girls schools across Bengal, enrolling 1,300 girls successfully, but also helped JE Drinkwater Bethune establish the first permanent girls’ school in India, the Bethune School, in 1849.

Jyotirao Phule

The fact that Jyotirao Phule, and his wife, Savitribai Phule, were the pioneers of women’s education in India is well known. Phule’s lifelong drive for women’s education stemmed from his own personal experiences as a Dalit man living in 19th century India. He realized that as long as the shudras, ati-shudras and women—all marginalized categories—were deprived of education, they would not be able to get a voice of their own, let alone develop as communities with self-respect and basic human rights. This idea was proved when Phule visited the Christian missionary school run by Cynthia Farrars in Ahmednagar (the institution where Savitribai also studied), and observed how much confidence the female students had gained.

So, in August 1848, Phule opened the first girls’ school in the house of Shri Bhide in Pune. It’s reported that on the very first day, nine girls from different social backgrounds enrolled at the school. Between 1848 and 1852, Phule and Savitribai opened 18 schools in and around Pune, all of them for girls as well as for children from Dalit families. What’s more, observing that many were unable to attend school because they worked during the day, Phule also opened many night schools by 1855.

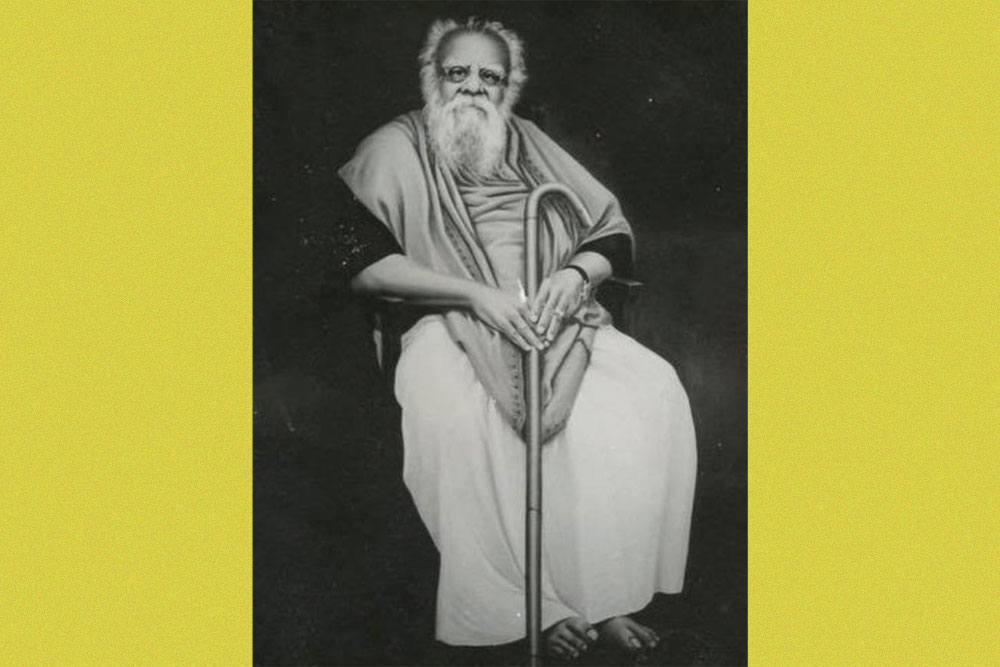

Periyar EV Ramaswamy

“Only education, self-respect and rational qualities will uplift the down-trodden,” the Dravidian social reformer EV Ramaswamy, popularly known as Periyar or Thanthai Periyar, is known to have quipped once upon a time—and never have words been truer, especially for women. You may not know much about this social reformer, but the work he did to advocate for women’s rights, especially right to education, vocation and property, is unparalleled in Indian history. Not only did he argue that ideas like chastity should not be unfairly heaped on only women, but also believed that women should have unhindered access to education, especially vocational education.

A scholar of ancient Tamil literature, Periyar used instances from these texts to prove that education is a basic women’s right. Not only did he actively campaign for women’s education, but also wanted it to be holistic with an inclusion of physical activity so that women develop physical strength as well as mental acuity. Further, he advocated that women should also be provided job-oriented education, and helped establish institutions like nursing schools and engineering colleges for women in Trichy and Thanjavur.

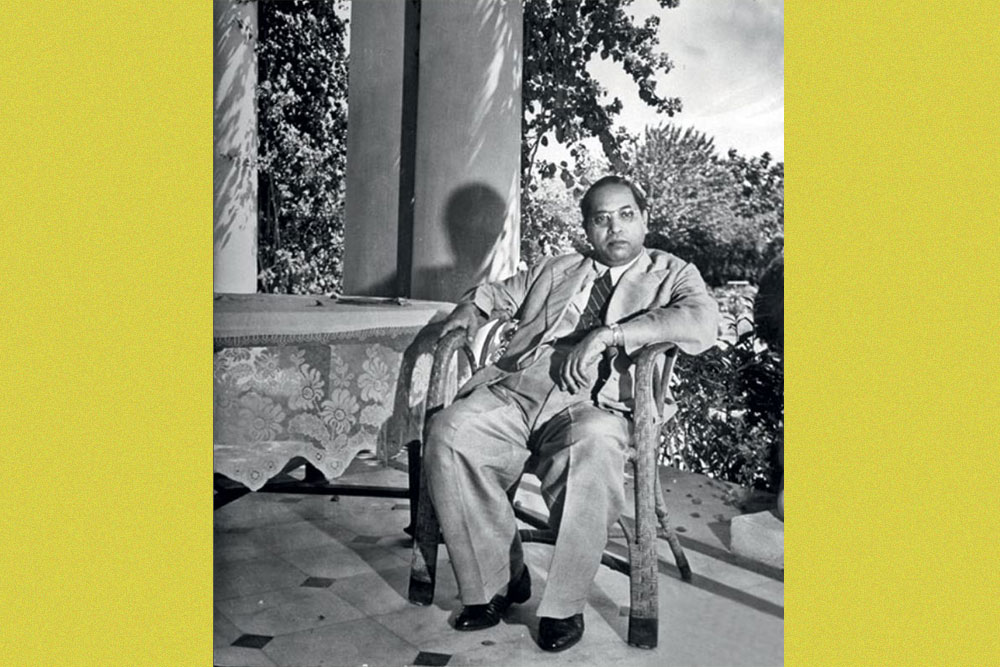

BR Ambedkar

Dr Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar is popularly celebrated as the chief architect of the Indian constitution, and also as an icon for the Dalit rights movements in the country. But Ambedkar believed that women have a key role to play in the emancipation of oppressed communities, and this could be done by ensuring their own rights to property and education. “I measure the progress of community by the degree of progress which women have achieved,” he said at the Second All-India Depressed Classes Women’s Conference held on 20 July, 1942. “I shall tell you a few things which I think you should bear in mind. Learn to be clean; keep free from all vices. Give education to your children. Instill ambition in them. Inculcate on their minds that they are destined to be great. Remove from them all inferiority complexes.”

To achieve these goals, Ambedkar advocated for women’s right to be educated along with men in the same schools and colleges, since it would ensure that both get the same quality of education. He believed that women’s education could help them achieve two purposes: their own empowerment, and the empowerment of others through them. However, Ambedkar argued against professional or vocational education as per the British education system, since it aims at creating a clerical nature of workers. His emphasis, instead, was on secular education for social emancipation and freedom so that depressed classes can enhance their social, economic and political status.

Leaders: Pandita Ramabai

Pandita Ramabai was a social reformer and educator who established schools for girls and widows. Her tireless efforts contributed to the upliftment of women through education. Pandita Ramabai was a social reformer and educator who established schools for girls and widows. Her tireless efforts contributed to the upliftment of women through education. Like so many other notable women leaders of their ages, Pandita Ramabai is a lady whose outstanding critique of society has been wiped from the mainstream history of India. As feminists, we must keep in mind that Ramabai's erasure from history is not an example of history being ignored or forgotten; rather, it is a conscious attempt to intentionally repress the voices of women who have spoken out against caste control and Brahmanical patriarchy. This emphasises how important it is to commemorate her life and work. Early in life, Ramabai became involved in the field of social change. She made extensive travels throughout Bengal Presidency and Calcutta, advocating for women's education and empowerment. She put in a lot of effort to free women. Her reputation as an educationist preceded her twenty years of age. She had travelled the nation with her brother to promote social reform and women education.

Leaders: Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan

Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the first Vice President and second President of India, was a proponent of women's education. He believed that educating women was essential for the progress of the nation and society. Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan is regarded as one of the greatest teachers of all time. Born on September 5, 1988, he put forth a lot of effort to become known as one of the 20th century's leading scholars.

Throughout his life, Radhakrishnan authored multiple works, some of which have become famous and have successfully reformed Indian society. He wrote a well-known book about Indian philosophy, the religion society, and the Hindu philosophy of life, for instance. Among the best writers in history, Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan has written for periodicals worldwide. In several methods, Dr. Radhakrishnan emphasised the need of women's education. According to him, women are civilization's missionaries. Radhakrishnan strives to give women a prominent position in society. According to him, broad education should be offered to citizens so they can live sensible lives. In academic labour, men and women are equally competent. He was also aware of the difficulties and impediments—poverty, prejudice, sexism, and violence—that women encounter when trying to get and pursue an education.

Leaders: Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddi

Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddi, India's first female legislator, was a strong advocate for women's education and healthcare. She made significant contributions to improving educational opportunities for women. Despite the odds, Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy cleared the Matriculation Examination. She had to enrol in the nearby Men's Second Grade College in order to pursue her higher studies because there weren't any hostels for girls. However, caste and gender prejudice fostered opposition to her academic prowess. The principal of the college objected, believing her presence would demoralise the male pupils. If she was permitted to join, several parents even threatened to remove their sons from the picture. Nevertheless, the Pudukkotai Maharajah silenced the critics and allowed her entry, exhibiting insight and progressive outlook. The Maharajah's historic choice represented a critical turning point in the history of women's education in South India. She was deeply affected by Mahatma Gandhi's inspirational leadership and the fervour of the Indian independence movement. She actively participated in the independence struggle, coordinated actions with other leaders, and was essential in the movement as a result of his influence. Considering, the social context of the day, Dr. Muthulakshmi realised that women could only attain gender equality via education. She joined the Women’s Indian Association in 1917, bringing her vision into line with pioneers such as Annie Besant, Hira Bai Tata, and Marget Cousins. She was also actively involved in the Madras Vigilance Society, the Muslim Women's Association, the Indian Ladies Samaj, and Madras Seva Sadan.

Leaders: Ramabai Ranade

Ramabai Ranade was a social worker and reformer who supported women's education and played a crucial role in establishing the Seva Sadan institution, which promoted women's empowerment through education. Similar to Savitribai Phule and Fatima Sheikh, Ramabai Ranade was instrumental in bringing women into the public sphere. Nevertheless, M.K. Gandhi referred to Ramabai as the epitome of “everything a Hindu widow could be”. Ramabai was born on January 25, 1862, in the Sangli district of Maharashtra. At the time, there was little spark in the feminist movement. Seldom were women able to pursue school or employment, much less stand up for chickenfeed rights, due to social, religious, and cultural restraints. However, Ramabai's unwavering power allowed her to see beyond the confines of her little community of Devrashtre. Ramabai Ranade, who was married to Justice Mahadev Govind Ranade when she was just eleven years old, found refuge with him. The latter, dubbed "The Prince of Graduates," was well-known for spearheading Maharashtra's social reform movement.

Their early marriage established the groundwork for their idealistic worldview, since their uneducated wife Ramabai was guided into a thorough education and training in spite of their family's disapproval. Govind Ranade, a genuine feminist ally, sent a young Ramabai to school, where she became proficient in Bengali, English, and Marathi.

Leaders: Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay was a multifaceted personality who made substantial contributions to women's education, arts, and culture. Her work included the establishment of cultural institutions that empowered women through education. Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay made significant advances in women's education, the arts, and culture. Establishing organisations like as the Crafts Council of India, the Central Cottage Industries Emporium, and the National School of Drama was made possible in large part by her. Additionally, Kamaladevi was instrumental in the founding of the All India Women's Conference, which promoted women's empowerment, education, and rights. She spent over five years in British prisons after becoming one of the first women in India to be jailed for civil disobedience. She gained knowledge of the daily struggles faced by Indian rural women and the value of locally produced goods manufactured by hand to the village's economy. These abilities might not only support a community on a local level but also develop into a distinctive international export. Sengeet Natak Akademi, National School of Drama, All India Handicraft Board, Craft Museum, Cottage Industries of India, Craft Council, India International Centre, and a refugee craft village outside of Delhi were among the organisations she founded with this understanding in mind.

Leaders: Aruna Asaf Ali

Aruna Asaf Ali was a prominent figure in the Indian freedom movement and an advocate for women's education. She believed that education was the foundation for women's progress and made efforts to expand educational opportunities.

Leaders: Mahadevi Verma

Mahadevi Verma was a renowned Hindi poet and women's rights activist. Her work extended to promoting girls' education and advocating for gender equality in education.

Leaders: Sulabha Deshpande

Sulabha Deshpande, a noted actress and social worker, was a strong supporter of women's education. She contributed to initiatives that aimed to provide educational opportunities to girls.

Leaders: Annie Besant

Annie Besant was a British socialist, theosophist, and supporter of Indian and women's rights. She played a significant role in promoting education for girls in India and worked to uplift the status of women through educational opportunities.

Conclusion

The legacy of these remarkable leaders who fought for women's education in India continues to inspire and guide us. Their unwavering dedication to the cause has led to significant progress in women's access to education, and their influence remains a driving force in the ongoing struggle for gender equality. As we celebrate their contributions, we acknowledge the importance of education in empowering women and building a more inclusive and equitable society.

FAQs:

1.Who was the first leader in India to advocate for women's education?

A-The history of leaders advocating for women's education in India is rich and diverse. One of the earliest proponents was Raja Ram Mohan Roy, who championed the cause of women's education.

2.Why is men's involvement important in women's education?

A-Men's involvement in women's education is crucial as it helps break down gender-based barriers, encourages inclusivity, and fosters a supportive environment for women's educational pursuits.

3.Are there any contemporary leaders in India working for women's education?

A-Yes, there are many contemporary leaders, activists, and organizations in India dedicated to promoting women's education and gender equality. They continue the legacy of those who came before them.

4.What were the challenges faced by these leaders in promoting women's education in India?

A-Leaders advocating for women's education in India faced numerous challenges, including societal norms, resistance to change, and limited resources. However, their determination and vision prevailed.

5.What is the current status of women's education in India?

A-Women's education in India has made significant progress, with increased enrollment in schools and higher education institutions. However, challenges such as gender disparity and access to quality education persist.

6.How can individuals contribute to the promotion of women's education in India today?

A-Individuals can contribute by supporting organizations that work for women's education, volunteering in educational initiatives, and advocating for policies that promote gender equality in education.

7.Who are some contemporary leaders working for women's education in India?

A-Several contemporary leaders, activists, and educators continue to work tirelessly for women's education in India. Their efforts contribute to further progress in this vital field.